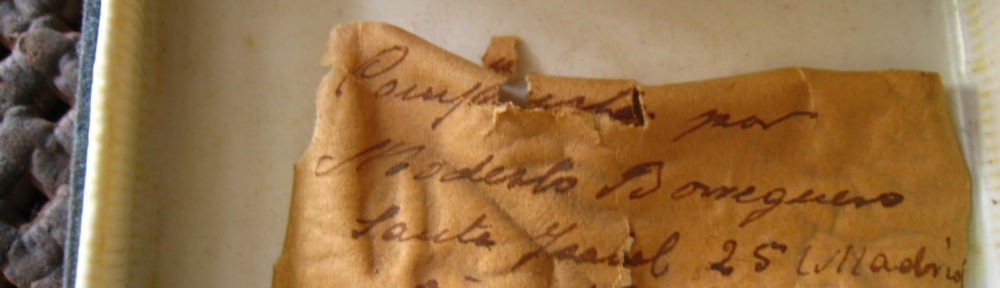

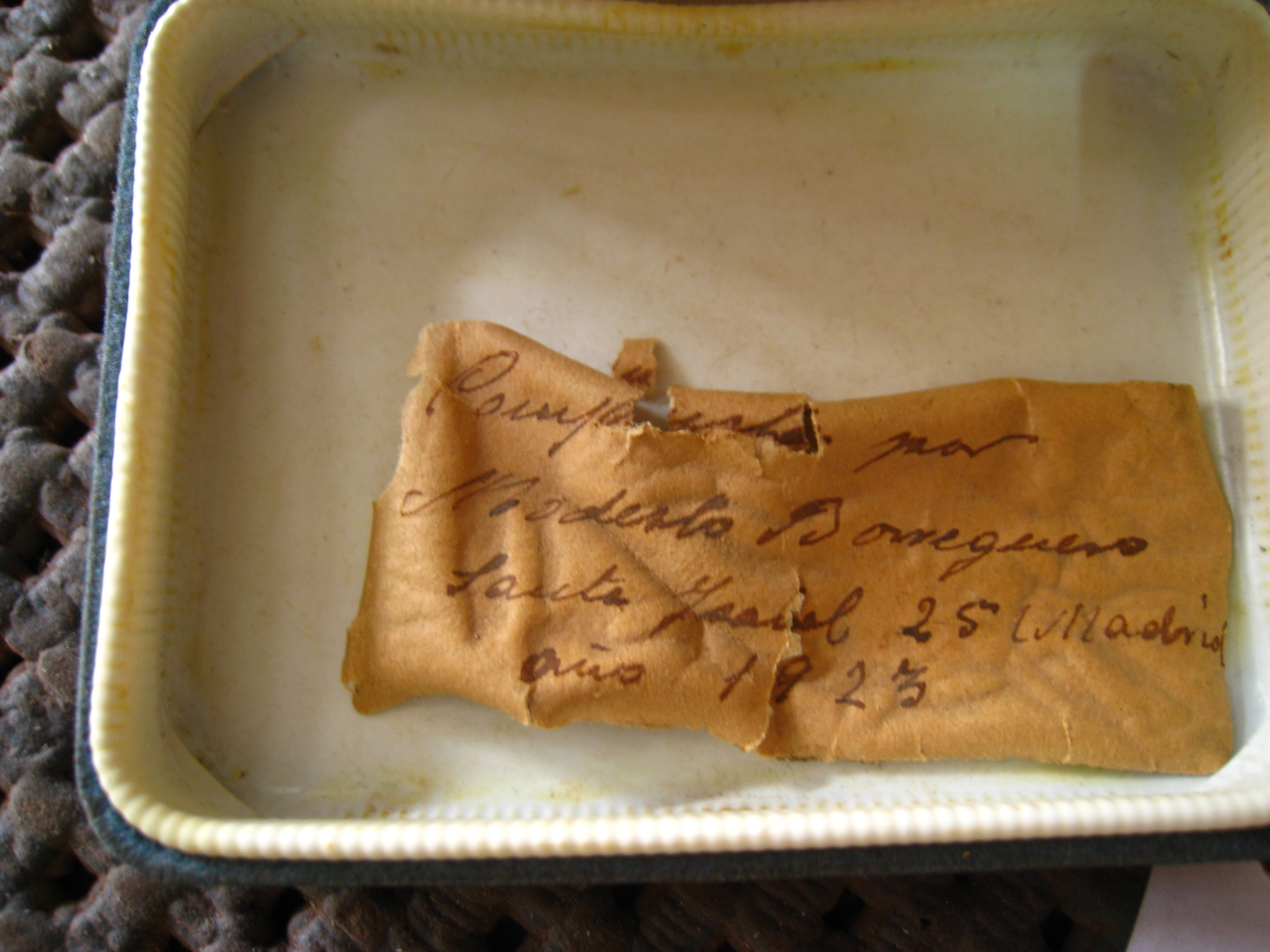

I am being called upon more and more often to appraise or at least identify historical instruments. The challenge is exciting and the necessary research is rewarding but you are very likely to find yourself on shaky ground if you want to give a conclusive answer. There are a few characteristics of a guitar which will immediately point to a particular maker: headstock shape, rosette pattern and obviously label and signature or stamp on the wood itself. José Luis Romanillos famously said that the label is the least reliable aspect when identifying a guitar. While it is true that a label can be removed, re-affixed inside a different instrument, or copied; we cannot always assume that there has been foul play so I might be a little more forgiving than Maestro Romanillos. The next step is to look for subtler characteristics in the building style that you have observed in other instruments by a particular maker. Already we are running into difficulties as most of us are intimately familiar only with a limited number of makers. In my case I would be hard-pressed to offer my expertise outside of the historic Spanish makers and even then, certainly not all of them. If a maker is not suggested by any of these characteristics we are left with the possibility of identifying an era or a school which might have produced this guitar. In Spain the most important schools or traditions were the Madrid, Granada, Valencia, Cadiz, and Barcelona schools. A careful study of the physical aspects of the instrument can usually determine which school it comes from especially since some of these traditions are limited to a certain historic period.

I am being called upon more and more often to appraise or at least identify historical instruments. The challenge is exciting and the necessary research is rewarding but you are very likely to find yourself on shaky ground if you want to give a conclusive answer. There are a few characteristics of a guitar which will immediately point to a particular maker: headstock shape, rosette pattern and obviously label and signature or stamp on the wood itself. José Luis Romanillos famously said that the label is the least reliable aspect when identifying a guitar. While it is true that a label can be removed, re-affixed inside a different instrument, or copied; we cannot always assume that there has been foul play so I might be a little more forgiving than Maestro Romanillos. The next step is to look for subtler characteristics in the building style that you have observed in other instruments by a particular maker. Already we are running into difficulties as most of us are intimately familiar only with a limited number of makers. In my case I would be hard-pressed to offer my expertise outside of the historic Spanish makers and even then, certainly not all of them. If a maker is not suggested by any of these characteristics we are left with the possibility of identifying an era or a school which might have produced this guitar. In Spain the most important schools or traditions were the Madrid, Granada, Valencia, Cadiz, and Barcelona schools. A careful study of the physical aspects of the instrument can usually determine which school it comes from especially since some of these traditions are limited to a certain historic period.

There are two almost insurmountable problems with appraisals in general. The first is the high incidence of vested interests either in the person of the owner (seller), the appraiser or the buyer. The pressure is on to assign a high value to the instrument for reasons of prestige or simple greed. This is common in the violin world especially because the “experts” are so often buyers and sellers of violins. The other factor that should be mentioned is the tendency to assume that a guitar-maker always uses the same techniques on each guitar. In reality it does seem that we can find commonalities between many of the instruments of one maker but at the same time we see similar commonalities within a school of different makers. However, we also see an evolution in the body of work of one maker and some unexpected experimentation within that same maker’s work. The result is that we might not recognize two guitars from different periods as made by the same maker.

In any case there is no substitute for experience and access to the largest number of guitars possible, detailed notes and photographs and access to a good network of experts in historic guitars by different makers as one person usually does not have expertise in very many makers.