Tag Archives: flamenco

The Irish Harp

I just got back from a holiday in Ireland. Highly recommended by the way. We had the misfortune to coincide in Dublin with the Aer Lingus College Football Classic so it was overrun with tourists. My son was amazed and very interested in the troubles which we heard all about on our trip to Belfast and Derry. Music was everywhere so of course it made me think of guitars. I often complain that none of the different levels of government here ever do anything to promote the guitar and guitar-makers despite Spain and specifically Granada being the most important centre in the world. Well the Irish do not have that problem. The official symbol of Ireland is the oldest conserved harp in the country (on display at Trinity College). According to our guide Ireland is the only country in the world which uses a musical instrument for its symbol. It just makes me think: Couldn’t we do something like that with the guitar? I suppose Spain could use the bulls, wine, paella, some iconic image of flamenco, a fan, windmills or olive oil but is there anything more universally Spanish than the guitar?

I just got back from a holiday in Ireland. Highly recommended by the way. We had the misfortune to coincide in Dublin with the Aer Lingus College Football Classic so it was overrun with tourists. My son was amazed and very interested in the troubles which we heard all about on our trip to Belfast and Derry. Music was everywhere so of course it made me think of guitars. I often complain that none of the different levels of government here ever do anything to promote the guitar and guitar-makers despite Spain and specifically Granada being the most important centre in the world. Well the Irish do not have that problem. The official symbol of Ireland is the oldest conserved harp in the country (on display at Trinity College). According to our guide Ireland is the only country in the world which uses a musical instrument for its symbol. It just makes me think: Couldn’t we do something like that with the guitar? I suppose Spain could use the bulls, wine, paella, some iconic image of flamenco, a fan, windmills or olive oil but is there anything more universally Spanish than the guitar?

Antonio Marín Montero

This year the guitar festival here in Granada includes an exhibition of photographs taken in the workshop of Antonio Marín. The photographer is Pepe Marín (not a family member). Once again Vicente Coves and the European Guitar Foundation are recognising important figures in the guitar community in Granada. Antonio was part of a change in the quality and professionalism of the guitar-makers in Granada in the 1960s that included others but for a number of different reasons he is the best known of those and any other makers here. The quality of his instruments, the number of guitars he has made and his generosity and sociability have made him what he is today.

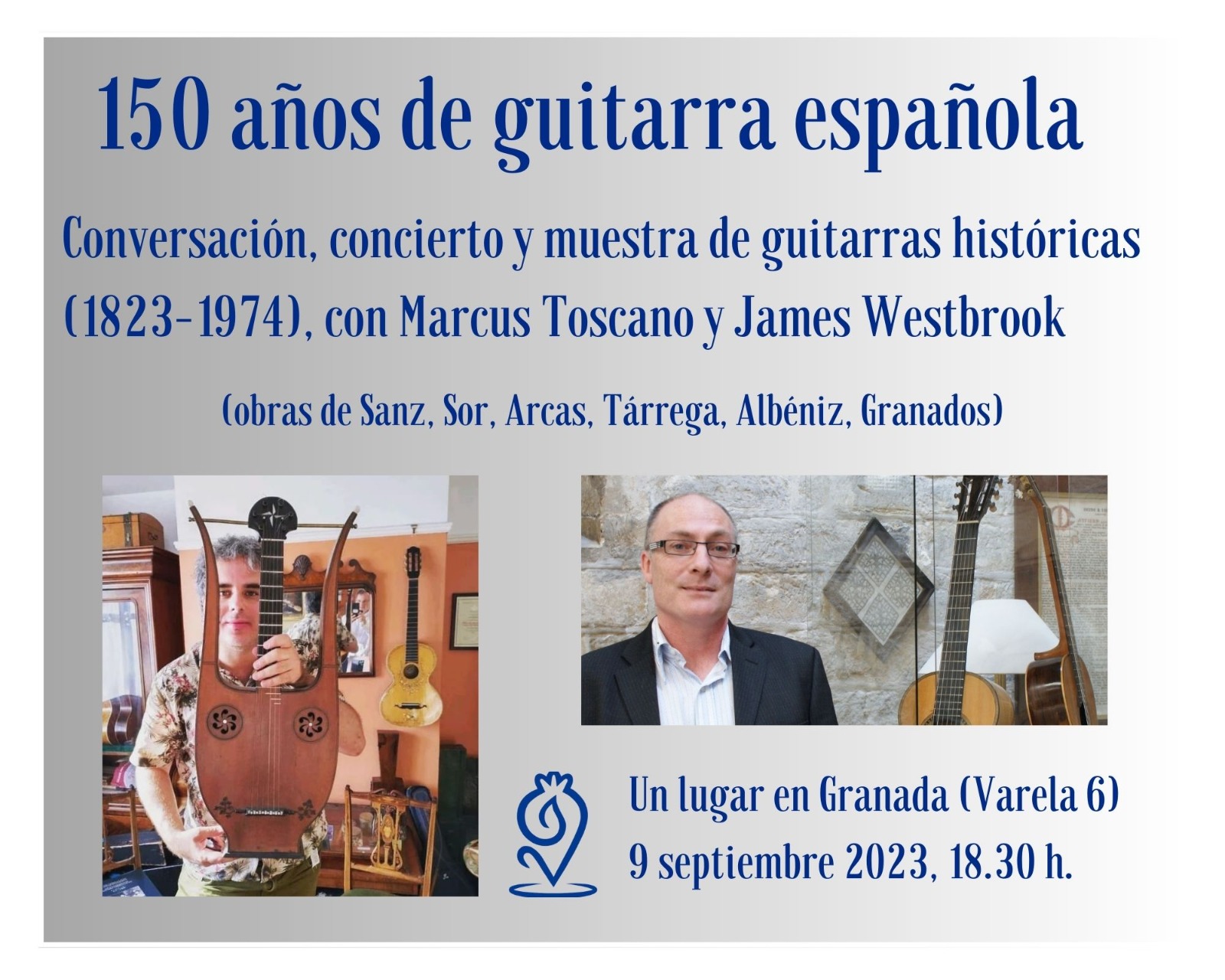

The poster for the exhibition is shown here with my friend Marcus Toscano; guitarist and Spanish guitar expert.

Cutting it Close

Nothing out of the ordinary today but I just wanted to illustrate how nicely this worked out. This back had some sapwood which is nice if symmetric but that was not the case. It was very narrow to start with so I had to use it with the sapwood. However, as you can see, I glued the narrow back on with very little margin for error but it worked out perfectly. The binding and purfling will just cover up the sapwood. I have some fantastic wood in my stock but most of it has some kind of detail that will make me have extra work when I use it.

Top jointing

The secret to a good glueing technique is to check if the joint is closed under pressure. Here in Granada some joints are tested by trapping a strip of thin paper between the two pieces to be glued while approximating the pressure that will be used to clamp it. This is common with the bridge and the fretboard. In these cases we are very interested in the edges of the joint as they like to peel up. This can involve removing a hint of wood from the inside of the footprint so that the edges are in solid contact while the rest is pulled in by the clamping pressure and the action of the glue drying. This is very subtle and you never remove so much wood that there is problematic deformation.

The secret to a good glueing technique is to check if the joint is closed under pressure. Here in Granada some joints are tested by trapping a strip of thin paper between the two pieces to be glued while approximating the pressure that will be used to clamp it. This is common with the bridge and the fretboard. In these cases we are very interested in the edges of the joint as they like to peel up. This can involve removing a hint of wood from the inside of the footprint so that the edges are in solid contact while the rest is pulled in by the clamping pressure and the action of the glue drying. This is very subtle and you never remove so much wood that there is problematic deformation.

With jointing a top or back it doesn’t matter what method you use but your planing should cater to the clamping method you use. Clamp the joint dry and test for movement all along the joint. I do this each time I glue one up. This is one of the reasons I use the method I do: it is quick for testing. If I “candle” the joint with no pressure there is a bit of light coming through the centre portion but with the clamping pressure applied it is difficult to shift all the way along.