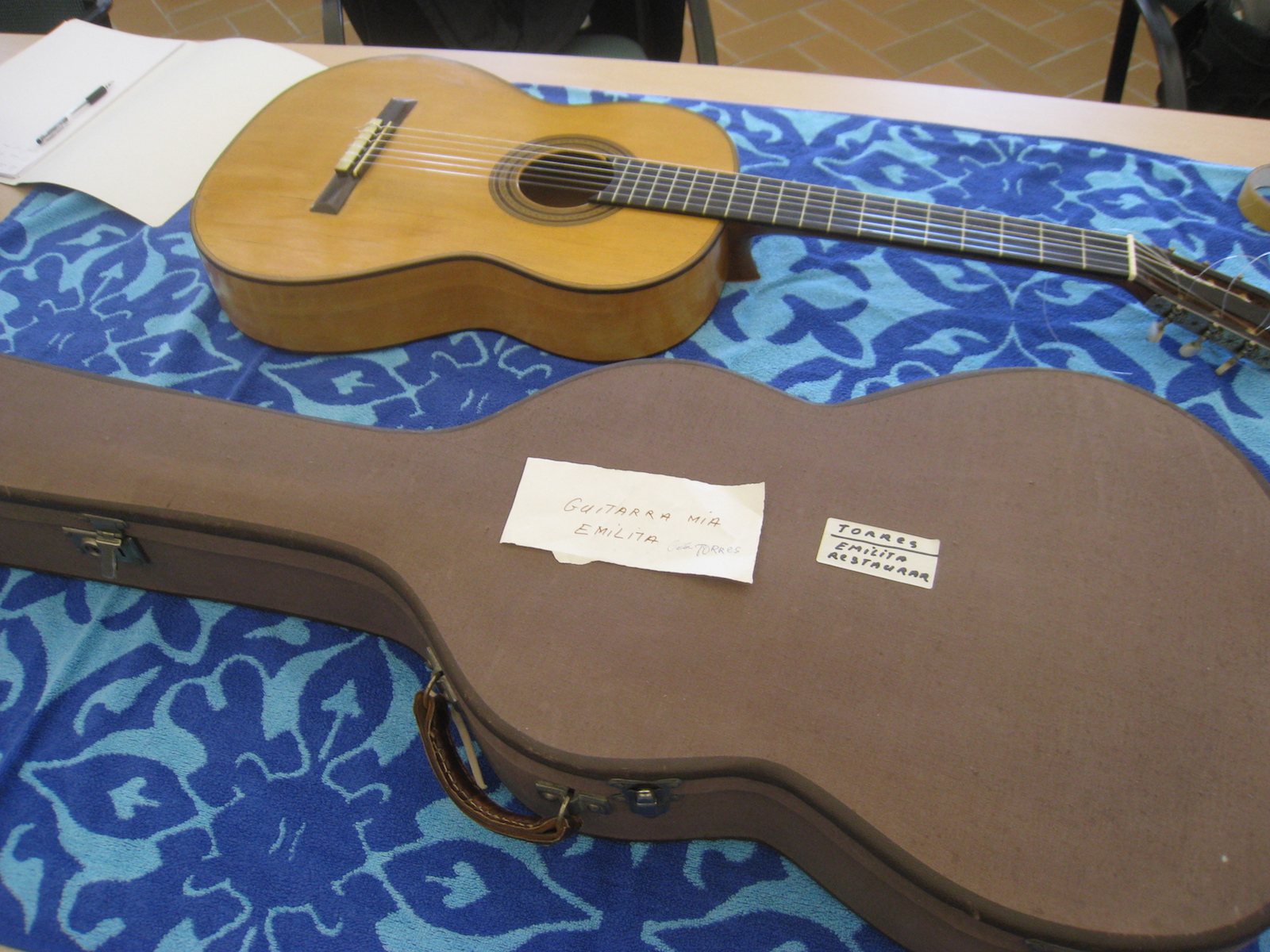

Here are a few more details about the Torres guitar that I have been studying at the Segovia museum in Linares, Spain. It is very well-preserved and does not seem to have suffered any great modifications except for the restorations commented below. This makes it a great instru

Here are a few more details about the Torres guitar that I have been studying at the Segovia museum in Linares, Spain. It is very well-preserved and does not seem to have suffered any great modifications except for the restorations commented below. This makes it a great instru ment for learning more about Torres and his style of working as well as getting an idea of his sound. This guitar doesn’t have the typical wear of long or hard playing, the damage seems to have come from humidity swings and perhaps an accident (broken side).

ment for learning more about Torres and his style of working as well as getting an idea of his sound. This guitar doesn’t have the typical wear of long or hard playing, the damage seems to have come from humidity swings and perhaps an accident (broken side).

There appears to have been two restorations carried out by two different people (in the second case I use the term restoration very loosely). The treble rib has a very well executed patch which is cleated on the inside very cleanly. I really can’t see how that could have been done without removing the top or back and there is no evidence to my eyes of that. Now I realize that it would be possible with such a large patch to place the cleats and then place the patch in an operation similar to replacing a rib. There is some glue squeeze-out to support that theory. The same hand seems to have cleated a few cracks on the top, again very cleanly and professionally.

The french polish covers the rib repairs very nicely so it is safe to say that there was shellac re-applied after that repair. The top is harder to judge but I would imagine that the shellac was also touched up there. I am glad to say that the top was not sanded to give a perfect surface and re-varnished at least not on the last repair. The bass rib also has an ugly crack which was re-inforced the first time with musical notation paper as is typical of the time. As far as I can see that is the extent of the first restoration.

What I believe to be the second “restoration” would be better described as an attack. White glue was use to glue brown veneer over a top crack and the bass side rib crack. In both cases it was stuck over previous repairs and so is bonded only in some places and open in others. Another top crack is splinted but in making the saw cut the repairperson cut right up to one of the braces and cut right into it. The bridge was taken off or was lifting at some point in time and has been re-glued. In this case hide glue was usedevidenced by some squeeze-out which was not cleaned up. The bridge was slightly damaged at its thinnest points and this is what makes me think it was during the second intervention despite the use of hide glue. There is also more hide glue mess inside the guitar than I would expect from the first

What I believe to be the second “restoration” would be better described as an attack. White glue was use to glue brown veneer over a top crack and the bass side rib crack. In both cases it was stuck over previous repairs and so is bonded only in some places and open in others. Another top crack is splinted but in making the saw cut the repairperson cut right up to one of the braces and cut right into it. The bridge was taken off or was lifting at some point in time and has been re-glued. In this case hide glue was usedevidenced by some squeeze-out which was not cleaned up. The bridge was slightly damaged at its thinnest points and this is what makes me think it was during the second intervention despite the use of hide glue. There is also more hide glue mess inside the guitar than I would expect from the first

restorer so maybe there were more interventions than two or some other possibility that I haven’t considered.The other thing that I think this person must have done is to fill and re-drill the holes for the tuning machines. In reality the slots are very badly cut also so the head is very hard to decipher.

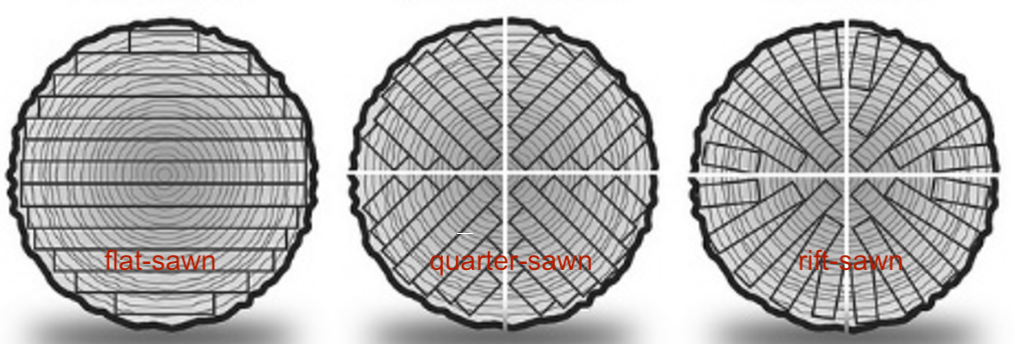

The joints between each of the three back panels are cracked completely to the point of cracking the re-inforcements too. I was unable to hear any vibrational noise when tapping or playing so I would be willing to leave those as they are. The quality of the back wood is not very good and I think this has contributed to the oblique cracks which can be observed in the waist area.

This all sounds terrible but actually cracks in a 150-year-old guitar are not a big deal if they are immobilised. Speaking of which, there is a long crack from bridge to rosette which needs to be immobilised and another beside the fretboard. These are susceptible to shearing and moving while under string tension and can not be left as they are. The other thing that needs to be dealt with is the setup. The nut is broken and only half of it seems to be present. The nut which is being used as a substitute has unevenly-spaced saw cuts in which the strings bind badly. The saddle has been supplemented with paper and wood veneer and needs to be replaced or supplemented in another way. The frets too should be examined and levelled if that is required. This is what I would recommend doing to this guitar in order make it playable. And this only because the owners wish to promote the Segovia legacy through concerts on his guitars. Any further work would cause the loss of the evidence of its history, including the hack who used the white glue on it. Of course it would be great to remove the veneer pasted over the cracks but in addition to going against the current trends of museum-style restoration, it might be very dangerous and necessitate removing the back. For a more in-depth view on current restoration criteria please see various publications by CIMCIM (International Committee of Museums and Collections of Instruments and Music) specifically by Robert Barclay. Another good source is “Adopting a policy of faithful copies of historically important musical instruments as an alternative to restoration.” (John Ray et. al.) in Wooden Musical Instruments: Different Forms of Knowledge. Paris 2018 Cité de la Musique.