written by Evaristo Valentí López

On a pleasant stroll around the workshops of Granada’s guitar-makers, we would probably all be surprised to find them occupied by tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed characters with curious Granada accents “contaminated” with the relics of their distant mother tongues, all performing a trade that descends from a deep-rooted, ancient Spanish tradition. For most of them, Granada is now their life and they have discovered a way, a path that some came here in search of and others fell into quite by chance in a leap of faith that ensnared them forever. In one way or another they have been received, sometimes adopted, sometimes trained, but all the close-knit family tradition that was guitar-making in Granada has been handed on to them in the manner peculiar to this trade.

The purpose of this article is to try to find out what these foreigners who settled in Granada and hereabouts have brought to this tradition, to the city and to the world of guitar-building in Granada.

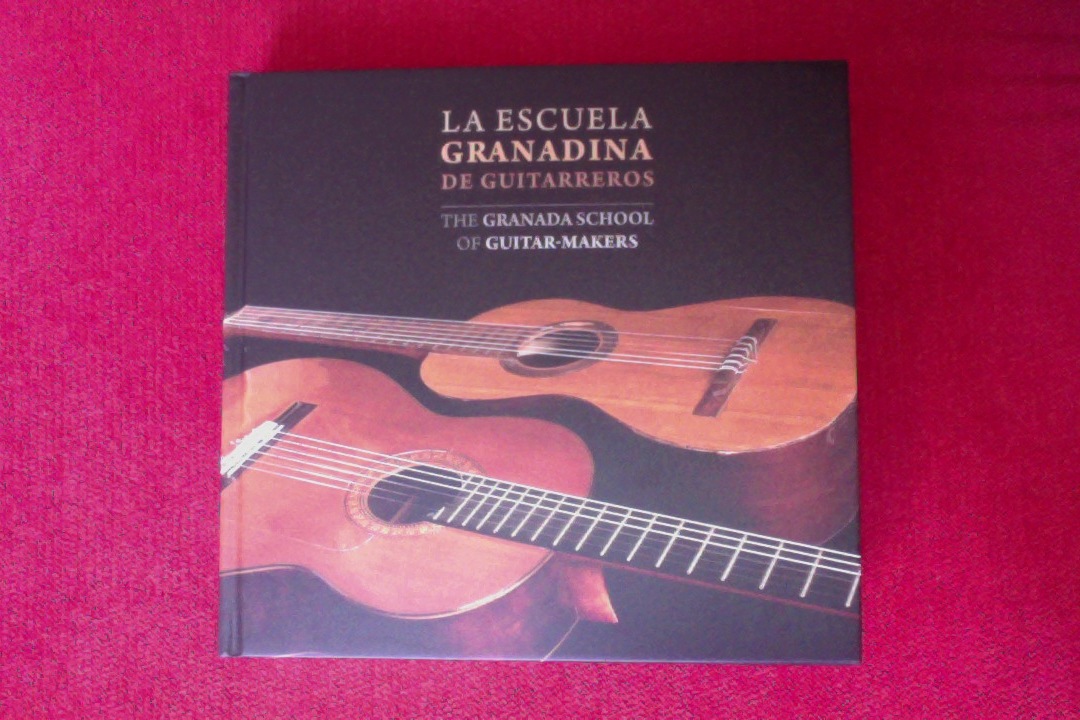

All those around the world who pride themselves on their knowledge of classical and flamenco guitars also know that a distinct tradition in the construction, evolution and development of this instrument was born in the city of Granada. As far back as 1500 there are records of violeros (luthiers) plying their trade in the city and it seems that their wisdom and skills were handed down from one generation to the next establishing a tradition that has endured to this day.

Although this is not our main objective, we will also try to establish a framework within which to situate the foreigners that came to our province to make guitars.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century Benito Ferrer founded what would later become an entire dynasty of guitar-makers bearing his surname, and since then the craft of guitar-building has gone from strength to strength gaining constantly in both quality and number. We now have three generations of guitar-makers building instruments and about fifty craftsmen in small workshops spread across the province working the guitar each with their own degree of skill and success.

The magnetic appeal of Granada soon becomes clear to anyone that consults a guide book or decides to take a wander around its streets. From the 1960’s onwards, in a Spain which was gradually changing, with all its complexes and prejudices, tourism became a part of our lives, a way of life for some people. Central Europeans in search of a different, more easygoing lifestyle began to arrive, among them a number of “stowaways”, people that had yet to find their place in the world and who were searching for alternatives.

Among those that became guitar-makers, we feel that the foreigners that arrived in Granada at that time shared a common motivation: the need to find an alternative approach to life, a new way of living that combined artistic creation (in which some were already involved) and personal craft work, which enabled them to capture in physical form a need for expression that had little to do with the typical jobs and lifestyles they could have opted for back home. Some of them, like characters in a children’s story that need to find their own path to resolve unconscious doubts and uncertainties and convert them into a solid base for their personal development, found the answers they were looking for in the modest workshops of the guitar-builders.

At that time, Granada already had guitar-makers beavering away in their workshops, who were highly skilled in the woodworking craft and had learnt to make guitars according to a long-established, deep-rooted tradition. This was a very special trade, with close links to the world of art and music (above all flamenco), for whom guitar-making was a way of life in itself. These were people who were not slaves to timetables or external obligations, beyond that of earning a living and enjoying life with the people that moved in the same circles as they did.

The first foreigner interested in guitar-building arrived in Granada at that time. Bernd Martin was 22 years old and was not shy when it came to asking for help or support. This German from Stuttgart was musically trained, owned a guitar made in Granada and already knew something about life in the city. He quickly contacted well-known traditional guitar-makers, who helped him make his first guitar and taught him to varnish the wood the way they did and indeed still do today. He was followed soon afterwards by René Baarslag, an engineer interested in playing the flamenco guitar, who discovered the craft by chance but was soon immersed in it; Alejandro Van der Horst, on holiday in Torremolinos, played the guitar and had built some without instruction, a person with a restless spirit in all senses of the word. Jonathan Hinves, an Englishman with some knowledge of music who had lived in various different places, met Antonio Marín when he came to him for help repairing a charango. He began making them himself and so entered the Granada guitar-making world. We are now well into the 80’s and this group already looks like one of the motors that will revitalize and dynamize the world of guitar-making in Granada.

At that time the imaginary family tree that had sprouted from the seeds of Casa Ferrer was divided into two branches with the workshops of Marín and Bellido and the other guitar makers who had trained with them before leaving to set up on their own. These, in very different ways, would go on to become the impromptu maestros of these young foreigners who were now making their first instruments and had begun exploring amongst ancient tools, amidst the mixed aromas of varnish, glue and tobacco for ideas that would inspire them and help them overcome the obstacles they found in their path.

These outsiders, fondly referred to as “guiris”, came across people with amazing woodworking skills, many of whom had been trained by cabinet makers with a high reputation, people who, far from finding the guitar a difficult object to make, were capable of improvising and coming up with solutions to problems which others had given up trying to solve and which would later became part of the magic of guitar-making, using the skills learned elsewhere. They were entering a closed, very particular circle, which was enormously individualistic and grew only very slowly through close friends and relatives, but which turned out to be generous when others turned to it in search of help. At the same time this route led to the solitude of the workshop where the craftsman had to tread his own personal path, sometimes without knowing what fellow guitar-makers were doing in their workshops often just streets away.

Bernd Martin sought help from José López, and also allowed himself to be influenced by the open, inquisitive mind of Germán Pérez. He also received help, as they all did, from the “Grand Master” Antonio Marín. René, Jonathan and Alejandro spent hours and hours in Antonio Marín’s workshop, gradually assimilating a way of working and of applying common sense to their craft. They came to him to learn the basics, and meanwhile they each worked separately and exchanged ideas and experiences with any traditional guitar maker they came across in order to try to understand why they did what they did.

For these newcomers to Granada making guitars was a lot more than just making a living. However, for the established guitar makers the need to find a market for their instruments had on occasions led them to make different types of instruments according to the prevailing fashions. In so doing they placed all their knowledge and fabulous skill at the service of what guitarists from all over the world required of them, so perhaps preventing them from establishing a clear personal line of work, a signature style by which they could be recognized.

At this point we should perhaps mention another illustrious character who left his mark on Granada’s guitar-makers through Antonio Marín. This is Robert Bouchet, an artist in all senses of the word and something of a legend in the world of guitar-making. In 1976 Antonio Marín saw and heard a Bouchet guitar and was surprised by its sound and noticed various interesting differences in its construction. The following year Bouchet spent a month in Granada and they made a guitar together. In fact, the Frenchman was not such a fine craftsman but he was a person with great artistic sensitivity (demonstrated in his painting) and a firm follower of the tradition of the best-known guitar makers (Santos, Manuel Ramirez). His methods were slow and complicated, but the great sensitivity of the two men led them to work together establishing a joint line of work and a strong friendship. Two years later, Marín travelled to France, where they worked together on various guitars to which each one contributed his long experience and skills (templates, designs, working methods…). We believe that although this relationship was not decisive in bringing about fundamental change, it did bring ideas to Granada, which some guitar makers have since used in their designs. In fact, today, some of Antonio Marín’s guitars are still based on their designs, and the influence of their work has also been passed on to others through Marín.

If we look at the dates we mentioned earlier, it would seem that a mini “revolution” took place at the end of the 1970s with the collaboration between Marín and Bouchet and the arrival of these highly motivated foreigners at the same time or shortly afterwards. This revolution however undoubtedly had little effect on the established workshops, who, confident of their own abilities, continued their work as an example for those from outside who were trying to learn.

This minor revolution was plotted unknowingly in the minds of the “guiris” who encouraged each other with their own very individual yet complementary personalities. The period when Bernd Martin, Rene Baarslag, Jonathan Hinves and Alejandro Van Der Horst all coincided in the city together with a number of other guitar builders who never quite settled in the province, was one in which Granada guitar making opened up once and for all to the whole guitar world. The quality of the instruments they produced reached very high levels and although each guitar-maker produced his own distinctive pieces, together they blended to create a standard which allows instruments from Granada to be identified anywhere in the world of guitars.

While Bernd worked closely with José López Bellido and Germán Pérez, René, Jonathan and Alejandro were in and out of the workshops of the most veteran guitar makers with Antonio Marín as a point of reference, at both a personal and technical level in all cases. The objective was always the same: to gain a sufficient level of skill to be able to work independently making guitars of the highest quality. To this happy band, we should also add the names of Kojiro Nejime and Thomas Redlin, the only ones who worked as true apprentices in the workshop of Antonio Marín. Nejime later went back to Japan where he continues to make guitars in the same style and Thomas no longer makes guitars.

It would perhaps be somewhat pretentious to brand such a small group of people as instigators of a revolution, especially when they themselves have never come to this conclusion. We will now try to justify this assertion by analysing the various factors that came together at the same time and were personified in these Europeans adopted by the city of Granada.

-They were all absolutely determined to improve, an objective which became an obsession that could not be let lie even for a moment. Everybody knows that restless, lively Alejandro could appear at any time of day or night to announce some little experiment from which he had drawn certain conclusions which may or may not have been useful, or Jonathan’s constant quest for perfection and beauty in detail.

-The friendship between them and the large number of hours they spent together led to mutual motivation and encouragement. They also shared some of their resources, which made the job a lot easier. It seems likely that this enthusiasm also rubbed off on the other guitar-makers in Granada, who saw their instruments becoming increasingly important, both within Spain and internationally.

-The fact that they came from other countries and spoke other languages made it easier for them to spread the word, to publicise their work and that of their maestros. They often travelled together to buy wood or to sell their guitars. They went to festivals and they contacted guitarists, whom they questioned exhaustively about their instruments and what they wanted from them, in order to get as much information as possible to help them accomplish their obsession: to make good guitars, according to the tradition of the workshops of Granada. At that time there were not so many good instruments outside Spain as there are today and they were part of the “voice of Granada guitar making”, who were conveying to the world their interest in a tradition learnt and assimilated through years of practice and transmitted within families from one generation to the next. The guitars they took with them on their travels were always well received and guitar players were eager to get their hands on them without the need for further explanations.

-The constant urge to experiment, always from within the bounds of tradition, led them to present new problems to the veteran guitar makers who, in an act of generosity, tried to solve them with their skills and experience. This tradition, the continuity of working on the same lines handed down through the centuries was one of the great attractions for the foreigners coming to Granada, something which they would later export as part of the identity of their instruments, along with the drive, the will to discover the best way of achieving the best guitar that this knowledge and these skills could create. Some of them think that the Granada guitar-making school is a type of sound and a particular way of work and organisation.

An additional external factor was that Dean Kamei set up a guitar business in San Francisco (USA) in 1974, discovering in Granada a type of guitar with a different sound, appearance, comfort and weight compared to the best-known guitars from other places in Spain. This discovery was important in that it brought in another outside influence that created interest and helped publicize the instruments being made here. Also, at the end of the same decade, Rolf Eichiger opened a shop in Germany. Interested in the guitar making tradition of Granada, he would later decide to come here to learn about it at first hand.

These are the main reasons that lead us to propose that during the last decades of the 20th century this small group of central Europeans, all educated in different atmospheres and cultures, became part of the motor that propelled the development of guitar building in the workshops of Granada.

Trips to Central European countries in cars weighed down by guitars became increasingly frequent for the guitar makers and exports to Japan and the United States also grew. At the same time in Spain, Casa Luthier in Barcelona began selling these instruments and “educating” potential clients in the taste for this kind of guitar, which, as we must recall was the result of the evolution of a tradition.

This growing interest led to a multitude of publications in American and Japanese magazines over the same period from 1980 to 2000, with reports about the long-established Granada guitar-makers and about the foreigners described here. The articles in these magazines always highlighted the same motivations: the great admiration for artisanal work based on tradition, represented above all by Antonio Marín and those who had been through his workshop and assimilated his vision of the guitar.

At this point I would like to go back to Rolf Eichinger, who ended up living out his last years in Granada, and whose peculiar influence was sufficiently great and well received. This German, who owned a guitar shop in his own country, became interested in the construction of instruments and decided to spend some time in Granada to learn more about the tradition and to work within it. The city later became his home. He was a most intelligent man with insatiable curiosity, who despite perhaps being less skilled (initially) at manual work than the best of Granada’s guitar makers, was blessed with a capacity for analysis and an organized vision of what he wanted from his guitars and how to achieve it. Personally, I think he kept the excitement, the enthusiasm that I spoke of when referring to Bernd, Alejandro, René and Jonathan very much alive. Until his death in 2009, he could be considered one of the last foreign guitar makers to have driven forward the development and dissemination of the guitars made in this city. Not always the pleasantest person in the way he passed on his ideas and knowledge and bluntly sincere on occasions, many of those who wanted to start making guitars who turned to him for guidance and are now enormously grateful for his “doctrine”. John Ray and Thomas Holt are both examples of the influence that Rolf had on guitar making in Granada.

If at the beginning of this article we explained its objectives (namely to analyse the contribution made by the first foreign guitar makers in Granada), we now feel it is necessary to make clear what the article does not set out to do. It is far from likely that the contents of this article provide new information or reveal new technical advances, nor is it an article of exhaustive investigation from which could spring other lines of research. It does however set out in a clear and orderly fashion the events that in different ways have helped shape the transformation of guitar making. We do not know what would have happened if these “guiris” had not come to Granada and we cannot possibly predict how guitar making in the city would have developed if they had not contributed to its dissemination throughout the world, what we can say though is that it would have been much more difficult without them.

Perhaps now what we should try to do is to sum up what has been said so far to establish exactly what they have left behind in Granada as a rich seeding ground for the generations of guitar makers that will come after them and assess the contribution of this small circle, which since the arrival of Bernd Martin in 1976, has worked, evolved and extended out to encompass the province as a whole. Perhaps in this order of importance:

-They disseminated throughout the world the type of guitar and the way of working in the workshops of Granada, thanks to their foreign contacts.

-They promoted the traditional base of sound and construction methods rooted in the guitar-making culture of the old Spanish schools, and above all, they produced high-quality instruments. With this premise, and without realizing it, they set precedents for other guitar makers and revitalized one of our essential crafts, which at that time, due to external influences, could well have fallen into decline. They even helped to recover certain methods which were gradually being forgotten and abandoned, and took the trouble to rescue them for posterity and return them to common use.

-The constant search for beauty in their work, trying to use the minimum number of elements to achieve a balance in all their instruments and the highest levels of quality. This idea, which may seem obvious, was not as simple as it sounds, in that from this period onwards not only did the quality of their guitars increase but also and equally importantly, they achieved a greater balance and consistency from one instrument to the next.

-A contagious enthusiasm for what they did, perhaps in a small world in which individuality and at times routine or even necessity had made work less exciting, more like a job. Their constant desire to evolve, to try out new things in an orderly, intelligent way and always with a sound base taken from the best guitars that the Spanish tradition was capable of producing. All of this was contagious and perhaps more importantly it obliged Granada’s established guitar makers, for whom Antonio Marín was the reference, to strive even harder to apply all their skills and knowledge to produce the best guitars they could.

-A fresh new approach to the trade. The “guiris” brought a breath of fresh air to this closed, tight-knit world of family clans with disperse, sometimes conflicting objectives. They became part of this guitar-making culture while at the same time bringing to it a new manner of approaching a job that was so deeply rooted in this area and had such particular customs.

As we have seen, the contributions made by the foreigners did not materialize in specific ways of doing things or innovations in the instrument. What they did achieve was to clarify and establish solid ground-rules on which to work (the Granada “guild” tradition), to take these ground-rules forward as far as possible and to take the guitars of Granada to a much wider audience, placing them in the highest quality niche that they deserve, with the maestros we discussed earlier as the guiding lights.

And so we come to the present day. Since our starting point, the 1970s, the world has been catapulted forward in the manner and the speed with which we relate to each other and we pass on knowledge in a way that none of us could possibly have foreseen. Spain and indeed Granada province have evolved in a similar way. In recent years visits from guitar makers from all over the world have become a constant feature and the direct influences of the maestros from Granada is gradually being diluted through the infinite, constant transmission of their ideas, spread through schools, courses and festivals in every corner of the globe. Almost everywhere there is a guitar maker we can see details in their guitars of the traditions in guitar building that we can see here. This is due to this continuous coming and going of people from outside who understand the importance of the guitar making that takes place in Granada.

From now on and with the increasing number of people making guitars in the province the spectrum is getting wider and wider, and any new idea is rapidly spread to the remotest regions of the planet. We do believe, however, that Granada remains a sort of bastion in which the ways of working of countless generations are renewed, updated and passed on. Foreign guitar-makers continue to flock here with the same enthusiasm, the same desire to keep the ball rolling forward, albeit slightly better informed thanks to these initial pioneers, and ready to commit their future to this most particular way of life. Henner Hagenlocher, Stephen Hill, Matteo Vaghi, Franz Butscher, Daniele Chiesa, Andy Marvi, John Ray and Thomas Holt are today an example of the next generation, who embarked here on a voyage of learning, of apprenticeship in the craft of guitar-making according to the traditional Granadino methods. Today they are open to influences from all the guitar-making schools from all the continents of the world but the vast majority are here to lap up the traditional customs and to keep trying to better understand that special sound and how best to use the different elements that come together to create it. They all aspire to that ideal which the foreigners discussed in this article respected, refined and enhanced.

(translation: Nigel Walkington)