A friend just finished a stint working for a local ice cream parlour and was telling us the other night about how they work. Just a few examples: The almonds they use are hand-sorted to ensure quality. The local strawberries are sourced from a single farmer. (Most of the strawberries in Spain are tasteless monsters often produced in greenhouses near Portugal.) This year they didn’t make their very popular blackberry ice cream because they couldn’t get enough of the fresh berries; frozen is not good enough for them. I myself have asked for orange sherbet and found on one occasion that it was not orange season so they didn’t have it and on another it was the beginning of the season and the oranges were still a bit tart. When I tasted it I was surprised to that this characteristic showed up in the delicious final product. This friend was very impressed with other aspects of how the business was run.

The spanish word “artesania” is much used and much abused but in its origin it referred to the traditional workshops where a trained professional produced functional articles that by their nature were unique and creatively made. These workshops were often associated and regulated through guilds. Ceramics, carvings, ornate furniture, leather goods, wrought iron, goldsmiths, blown glass, marquetry and instrument-making are just a few examples. These artisans persisted because there was a need for the product, the quality was very high and of course cheap industrial processes did not exist. In different historic periods there have been resurgences of artisanry for reasons of increased wealth and patronage by the nobility. Those examples that have survived into today’s industrial world have done so usually because of the quality of the work and the demanding clientele who are not satisfied with what industrial production has to offer. In order to make a living at such a time-intensive occupation the artisan must be well-organized, efficient and must be able to charge much higher prices for his products than the same product produced in an industrial setting.

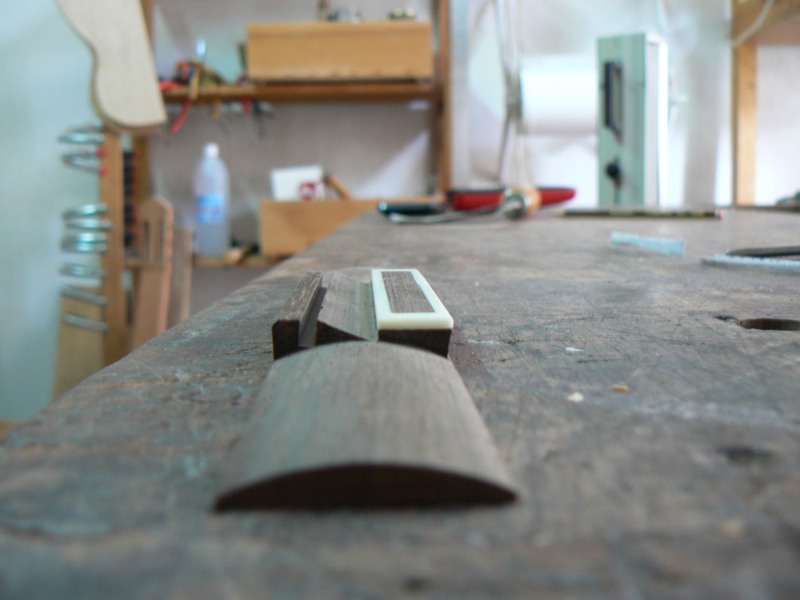

My favourite example is, of course, guitar-making and one of the oldest examples of this tradition can be found right here in Granada. Fine guitars are often referred to as “handmade” in part as a translation of the spanish term “artesanal” but the definition of the spanish term is not about the absence of machines but rather the absence of industrial processes. Artisans of old used the best technology they could and often showed great ingenuity in developing new ways to lend more efficiency to the work without detriment to quality. I dislike the term handmade because it gives the impression that we use no machinery in our work. We too use the best technology we can but we control every step and integrate it into the whole process. In most cases the guitar-makers here work alone unless they have an apprentice. It is this hands-on, total responsibility for the process that makes these guitars so much better than a factory product. As I have said before, the factories will never reach the quality that we can for the simple fact that profits will always be the driving force. They can theoretically train someone to make a guitar as good as ours but when they see the time it takes that one person to produce one guitar while their production lines do nothing (for that guitar) it doesn’t make economic sense. So they will take advantage of the production lines for the less important tasks until they realize that in guitar-making every task is of the utmost importance. Now back to the ice cream analogy: the quality of the ice cream I was talking about earlier is fantastic, their dedication to quality, sustainability and eco-friendliness pays off and everyone wants their ice cream (much more expensive than the competition of course). In my mind it is this constant striving for quality that makes the handmade guitar so much better. So, the definition of handmade must be qualified to refer to the process of one maker choosing the wood, seasoning it, using his tools (electric and otherwise) to thickness the components, design and bring to fruition the aesthetics of the instrument, and most importantly transform the pieces of wood into something magical which has the potential to stir our emotions like nothing else.

Here is a video made with a guitar which inspired me to make a copy of it this year.

Deuxième Arabesque de Claude DEBUSSY (arrangement: J. Riba)

“In the spring of 1913, Andrés Segovia decided to seek his fortune in Madrid, and gave a recital in the Ateneo the evening of May 6 […] The programme did not seem so different from those of the followers of Tárrega but it contained a surprising novelty: The transcription—by Segovia himself—of the second of the Deux Arabesques for piano by Claude Debussy […] This audacious move revealed very clearly the aspiracions of the young Segovia to place himself in a different category than the rest of the guitarists — looked down on by musicians and practically ignored by learned audiences—and his intention to play a leading role in the artistic circles of his time.”

Angelo Gilardino,

extract from the liner notes to the CD “Aljibe de Madera,

Homenaje a Andrés Segovia” Tritó TD0094